Research provides generalized insights and estimates of effect sizes across contexts. Policymakers and educational leaders want to scale practices with positive effects quickly and efficiently to maximize the benefit of research for schools. All too often, however, this results in top-down, one-size-fits-all professional development, providing little opportunity for teacher agency. Nor does it provide leeway for the kinds of contextualized, district-specific adaptations required for research these practices to be as effective as they could be. Over the past decade, our work has sought to tackle this dilemma. We have tried to develop adolescent literacy professional learning experiences that empower, engage, and inform participating teachers.

Our (Josh’s and Jacy’s) understanding of adolescent literacy development and instructional coaching was grounded in our academic training and teaching at Harvard and our work as teachers and coaches in urban public schools. Since then, we have continued adapting our approaches for responsive, professional learning and instructional coaching in individual schools and districts. While we quickly found great success in localized pockets, we soon realized that our ability to co-construct collaborative, engaging adult learning environments focused on research-based literacy practices would be limited as we tried to scale across districts and states. Very few mechanisms were initially available by which powerful, engaging, teacher-centric professional learning could be shared across school sites.

Then, in 2021 and 2022, with support from IES and the Comprehensive Literacy State Development (CLSD) grants in Ohio and Wyoming, we began to develop and pilot a new model. We explored how technology could be used to support a group of 17 middle and high schools to implement our well-established adolescent literacy professional development content in a radically decentralized model that leveraged technology to empower site leaders in each school. The early results of this work suggest that specific affordances of this model have wide implications for supporting teacher engagement in learning (Snow & Lawrence, in press). Here, we review three dimensions of this work and contextualize these findings within a larger discussion of how school leaders can and must build teacher collaboration and engagement and thus support teacher well-being and retention.

Instructional Delegation and Team Building

One of the biggest challenges we originally faced in scaling our interactive, teacher-centric professional learning across a dozen districts in several states was that we needed to establish structures to ensure that we, and the school leaders we worked with, had our “ears to the ground.” Of course, the leadership literature suggests that we would be wise to establish teams of collaborators when engaging in organizational and instructional change (Bryk, 2015; Woulfin & Spitzer, 2023), but this collaborative/team-building design features forced creative thinking when considering scale across schools, districts, and states. Upon reflection, paying attention to delegation and building/harnessing local expertise across schools and districts turned out to be one of the most powerful moves we made as we began exploring more technology-focused adolescent literacy professional development.

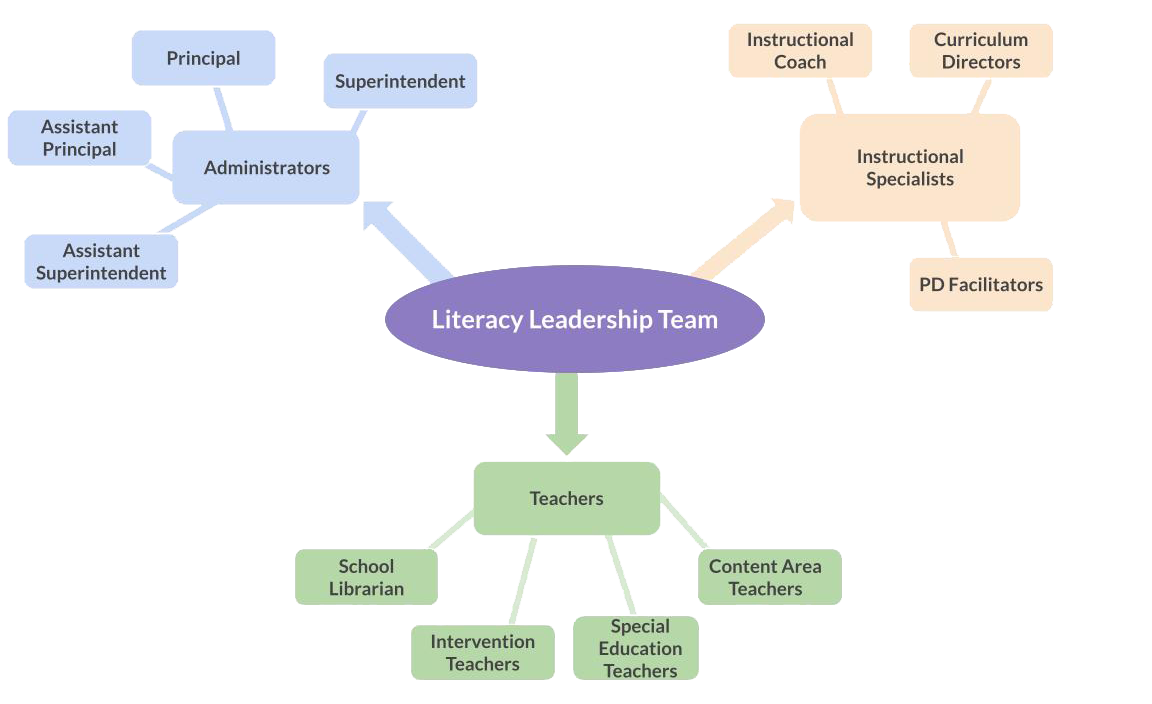

Delegation initially took two forms: The first was the establishment of a Literacy Leadership Team at each school site that included administration, teachers, and other locally-selected representatives (Figure 1). In some cases, schools had established these teams as a part of writing the school's CLSD grant application. In other cases, teams were established at the onset or in the course of the professional development work.

Table 1 presents team composition in five of our partner districts. The importance of this structure was demonstrated in one of our partner districts in an interesting way. In this district, teachers were involved in the CLSD grant application and setting the agenda for the literacy work, but not in a highly public manner. When we joined the project, exit surveys demonstrated that many teachers felt they had no voice in the initiative. The district curriculum lead and school principal (re)convened the literacy leadership team with a more public mandate. The team met and gave detailed feedback on the professional learning goals and specific structures we implemented that year. The feedback resulted in specific changes to the plan and marked improvement in teacher engagement in the larger project. Naturally, we all feel more comfortable confiding in some of our colleagues and less comfortable sharing our feedback with others. A leadership team for any professional learning initiative creates more opportunities to collect feedback and a public structure to demonstrate that this professional learning is a shared endeavor.

In our projects, we also recruited one or two teacher leaders at each school site to lead efforts on the ground. In some cases, these teacher leaders were literacy coaches; in other cases, they were teachers who were given schedule flexibility and the title of site leader or lead learner for the project. Across sites, their goal was to prepare and facilitate professional learning conversations. They were not expected to be experts on evidence-based literacy instructional strategies. In fact, they were specifically asked not to take the role of “expert” since we wanted to encourage a stance of collaborative teacher inquiry and agency. Instead, these site leaders lead the work as facilitators and supporters. They met with us to understand the role of peer coaching and instructional coaching (drawing on the work of Bean & Ippolito, 2016). The site leaders were supported with a set of discussion protocols and technology tools, and met virtually as a group (from across districts) to talk about challenges and celebrate victories on a monthly basis. For teachers at each school, these leaders, not our research team, represented the face of the work. These leaders, not us, established what the research looked like in practice in their respective school communities. We found it relatively easy for our site leaders to build interest and engagement in evidence-based adolescent literacy strategies by utilizing the discussion protocols and peer coaching strategies. Interestingly, about 20% of our schools selected former math teachers to lead the work. Despite a limited foundation in literacy research, these leaders were taken seriously by the content area teachers when they articulated how the science of reading can be applied to improving content area learning outcomes.

.jpg)

Instructional Coaching

Instructional coaching has the potential to address both the problem of low student performance and the problem of limited teacher understanding when delivered with fidelity and at scale. Instructional coaching involves creating school conditions for professional learning and produces additional benefits related to teacher well-being and retention. Specifically, coaching provides opportunities to improve school conditions for teachers in at least four areas:

- Opportunities for teacher feedback in planning. Teachers report higher well-being and are more likely to stay in the profession when the leadership addresses their concerns. Site-based coaching is one of the few formats that allows teachers to share their classroom experience with instructional practices directly with instructional leaders and colleagues (Johnson et al., 2012; Ladd, 2011).

- Teacher mentorship. Mentorship programs have strong effects on teacher retention (De Jong & Campoli, 2018; Ingersoll & Smith, 2004). For new teachers, coaches can play the role of instructional support and also career mentors. In one of our partner districts, new teacher turnover was fifty percent last year. Surprisingly, none of the new teachers in our professional learning initiative left the district. These results suggest limited, anecdotal evidence that the collaborative mentoring opportunities we established supported new teacher well-being and retention.

- Sustained opportunities for collaboration. Teachers report higher levels of job satisfaction and are more likely to remain at schools where they can collaborate with their colleagues (Johnson et al., 2012). A large evaluation of a coaching program for written language instruction documented that teachers' participation in coaching was associated with providing more help to colleagues on instructional planning; the influence of coaching on participants' instructional practice diffuses through a network of helping (Sun et al., 2013).

- Opportunities to apply what is learned. Teachers are more professionally satisfied when they are held to high professional standards for delivering high-quality instruction and receive feedback that could help them improve their teaching (Johnson et al., 2012). Although teacher evaluations are important and align with the goals we established in our professional learning, it is not a vehicle for iterative and supportive feedback. On the other hand, site-based coaches can give regular feedback and tailored suggestions in non-evaluative ways and can differentially support teachers in implementing instructional changes.

Just as importantly, site-based instructional coaching is impressively effective in improving teacher instruction (d = .631 [26], SE = 0.083) and student achievement (d = .281 [15], SE = 0.061), but only in smaller studies (those with fewer than 100 teachers involved; Kraft et al., 2018). Unfortunately, larger coaching initiatives have yielded smaller effects. Our initial results suggest that our decentralized model provides enough support that new “coaches” can be effective while learning the ropes.

Using Technology for Efficiency, Consistency and Visibility

There are some obvious challenges with implementing a more distributed process for professional learning in which you delegate more control to local leaders rather than relying primarily on outside experts. The first challenge relates to providing clear, consistent, and accurate information. Traditional “train the trainer” models often fall apart under pressure from challenging teacher questions about modifying and adapting practices to fit student and contextual needs. Our model used an online learning platform to present a structured series of videos, podcasts, and readings from leading researchers to ensure that the essential research-based information was consistently shared with all site leaders and teachers.

A second (and related) problem is finding time to collaboratively reflect on and discuss research-based information and consider how it can be applied in our school communities. In our project, we would release research-based content first, and all participants would respond online at least one or two days before at an in-person face-to-face meeting led by the site leader. Before the in-person meeting, the site leader reviews teacher responses and uses these responses to anticipate issues, prepare specific resources of teachers, and set the meeting agenda (this process is explained in depth in the site leader walkthrough of the Reading Ways learning platform). The precious time that our site leaders had with their teachers was spent discussing their responses and thinking about applications. Teachers found that this use of their time was much more engaging and productive than when they were asked to digest large amounts of information and think about applications in half-day or full-day formats (to learn more about the teacher experience, check out the teacher walkthrough of the Reading Ways learning platform).

A third challenge to scaling a distributed model of coaching relates to stakeholder visibility. When Josh and Jacy began this work we “delivered” a significant amount of our content in summer institute or other time intensive formats. We did not have the capacity to schedule the number of follow up visits and meetings that we would have liked. Although participants reported great appreciation and enthusiasm for our work together both in personal interaction and anonymized feedback, we had limited visibility into ongoing teacher engagement and implementation of the practice we were hoping to scale. By using a distributed, collaborative learning environment to support the project, we were able to generate data dashboards that helped keep administrators, site leaders and our development team up to date on teacher participation in meetings and use of online resources.

Final thoughts

Our journey illuminates the nuanced transition from educational research to impactful classroom practices. Central to this transition is a decentralized approach that prioritizes teacher autonomy. The establishment of Literacy Leadership Teams and the strategic use of technology exemplify a successful blend of structured, research-driven instruction with the necessary flexibility for teachers to adapt these methods to their unique classroom settings. This approach not only bolsters teacher agency but also fosters a collaborative environment where teachers feel their contributions are significant and respected. In the current, complex educational landscape, our model stands as a viable solution for schools and districts seeking to reinforce teacher agency, offering a balanced framework that allows educators the freedom to innovate while adhering to research-based guidelines. This work aligns with ongoing work about the importance of adapting implementation to school needs (Lawrence et al., 2017) and how the coaching can help adapt specific practices to school contexts to support equitable learning (Ippolito & Bean, 2024). Our efforts add to the growing body of evidence that when teachers are empowered with the autonomy to customize research-based strategies to their specific needs, the result is a more engaged, effective, and sustainable teaching practice.

References

- Bean, R. M., & Ippolito, J. (2016). Cultivating coaching mindsets: An action guide for literacy leaders. Learning Sciences International.

- Bryk, A. S. (2015). 2014 AERA distinguished lecture. Educational Researcher, 44(9), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x15621543

- De Jong, D., & Campoli, A. (2018). Curricular coaches’ impact on retention for early-career elementary teachers in the USA. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(2), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmce-09-2017-0064

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Smith, T. M. (2004). Do teacher induction and mentoring matter? NASSP Bulletin, 88(638), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263650408863803

- Ippolito, J., & Bean, R. M. (2024). The power of instructional coaching in context: A systems view for aligning content and coaching. The Guilford Press.

- Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 114(10), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211401004

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018b). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

- Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373711398128

- Lawrence, J. F., Francis, D., Paré-Blagoev, J., & Snow, C. E. (2016). The Poor Get Richer: Heterogeneity in the efficacy of a school-level intervention for academic language. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(4), 767–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1237596

- Snow, C., & Lawrence, J. F. (in press). Opportunities to learn and intersubjectivity. In O. Erstad, B. E. Hagtvet, & J. Wertch (Eds.), Education and dialogue in polarized societies: Dialogic perspecitves in times of change. Oxford University Press.

- Sun, M., Penuel, W. R., Frank, K. A., Gallagher, H. A., & Youngs, P. (2013). Shaping professional development to promote the diffusion of instructional expertise among teachers. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 35(3), 344–369. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713482763

- Woulfin, S., Stevenson, I., & Lord, K. (2023). Making coaching matter: Leading Continuous Improvement In Schools. Teachers College Press.